10 things you might not have known about St.Cyprian

“Once upon a time myths and legends were understood as historical records.”

While waiting for the arrival of Rubedo Press’ Cypriana:Old World, I used the time to revisit some of the books on St.Cyprian of Antioch that were already waiting on my bookshelf. Next to JSK’s Testament of St.Cyprian and several general books on saints and folklore I rediscovered a worn old softcover volume from 1927.

I vaguely recalled buying it years ago when researching on the origins of the Faust legend. Thus its title was little surprise: ‘Greek sources of the Faust legend. The magus Cyprianus. The account of Helladius, Theophilus.’

In this small book the classical philologist and once professor at the universities of Greifswald, Münster and Vienna Ludwig Radermacher (1867-1952) provides an in depth account of the legend of St.Cyprian of Antioch and examines its ties to older Greek sources.

Diving into it and being amazed by the wonderful scholarship and exegesis Radermacher provides, I came across two other little known German sources on St.Cyprian from the late 19th and early 20th century. These are Richard August Reitzenstein’s detailed article ‘Cyprian the Mage’ from 1917 as well as Theodor Zahn’s liminal study and reconstruction of the source text ‘Cyprian von Antiochien und die deutsche Faustsage’ (1882).

As all three articles are available in German only, I thought I’ll share a few things that stood out for me while immersing myself in these slightly older publications. Due to their academic authors all of the points below are looking at the historic tradition of St.Cyprian - rather than the practical devotional side of working with this inner contact. Yet despite the academic background, we will still hear about Apollonius of Tyana, the Greek Magical Papyri as well as a Greek satire that might have well paved the way for Cyprian's own legend....

Here we go. I hope it wets your appetite just as it did mine to dig deeper into JSK's massive double volume as well as the currently shipping Cypriana: OldWorld.

LVX,

Frater Acher

10 Things you might now have known

about St.Cyprian of Antioch:

(1) The literary tradition of Cyprian and Justina is originally based on three different versions of the story by three different authors. The first one tells Cyprian’s conversion to Christianity and is mainly focussed on Justina and her immense spiritual powers granted to her due to her strict piety. The second story centres on St.Cyprian’s repentance; it begins as a speech of the remorseful mage and later turns into a first-person account of his tale. The third one focusses on the famous martyrdom that both the saint and Justina had to undergo, which is not mentioned in either the first or second version of the legend.

(2) Around the middle of the 5th century the Empress Eudokia brought all three versions together, had them translated into a metric paraphrase and published them in three books. Large fragments of the first two books are still available today; we also hold an abstract of all three books from the 9th century. Based upon the vast archive of subsequent retellings of the legend it was possible to re-construct the original text of the first book; for the second and third book we do no longer have access to the entire original source texts.

(3) In addition to these source texts one of the earliest references to St.Cyprian stems from the 4th century church father Gregory of Nazianus. In September 379 in Constantinople he held the sermon in honour of Cyprian on the saint’s special day. While this sermon mentions little about the historic person of Cyprian of Antioch it already mixes aspects of his biography with the one of Cyprian of Carthage. According to Reitzenstein it is Nazianus’ early blending of these two stories - the one of St.Cyprian of Antioch and the bishop of Carthage - that might have led to all the subsequent confusion in the Greek textual tradition. Finally, it’s important to call out that the martyrdom of St.Cyprian and Justina does not yet feature in Nazianus’ sermon. Thus it is likely that it was either not known at the time yet or simply added as a literary fiction later on.

(4) Due to its strong resemblance to other, older legends it is assumed by Reitzenstein and others that the story of St.Cyprian and Justina is not based upon historic events or people. More likely it is utilising narrative plot elements that were familiar at the time to mock pagan philosophers, theurgists in particular and to promote the power of the Christian faith over all ancient gods. Two main sources of the legend are both from the second century and indicated as the apocryphal ’Acta Pauli et Theclae’ as well as Lucian of Samosata’s Philopseudes (Lover of Lies).

(5) While the initial plot of Lucian’s novel is almost interchangeable with the later story of Cyprian and Justina, the legend of our saint was turned from a satire into a seemingly more authentic and realistic story. Here is an example: in Lucian’s story a nameless Hyperborean mage during a new moon night summons both Hecate as well as Selene for his client Glaukias. Hecate appears in the company of Kerberos, Selene in many shifting forms such as a bull and a dog. Both goddesses stay bound for the entire length of the ritual - during which the mage creates a clay figure, breathes life into it and sends it out to bring the desired virgin. After Glaukias and the young woman finally have made love for the entire night - under the interested gaze of a philosopher, a mage, two goddesses and a love-demon made from clay - both Selene and Hecate are finally released back into their celestial and chthonic realms. — In other words, as even Radermacher remarks in 1917, the mage is literally moving heaven and hell just to offer the young lad a sexual adventure. The whole story becomes even more ludicrous considering the name of the young lady is a Greek name that was known to belong to hetaerae, i.e. prostitutes. This is precisely the humour Lucian's leverages in his other satires as well.

(6) All three authors agree on the fact that St.Cyprian and Justina’s legend is not a tale against magic as such. Quite the opposite - it is a tale meant to illustrate the supreme power of Christian (white) magic over the old pagan cults and demons. Only through the direct divine intervention of Christ is it possible for the faithful ascetic (Justina) to overthrow the classical theurgist and the attack of his pagan demons. Both parties though believe in and leverage their own form of magic. The legends therefore has to be read as part of a wide network of narrative traditions which illustrate a trial of strength between an old established power (Cyprian) and a newly emerging one (Justina) overthrowing it.

(7) Especially the second source text aims to introduce similarities between Cyprian and the life of Apollonius of Tyana: Where Apollonius was introduced to the service of Asclepius early on in his childhood, Cyprian was introduced to Apollo. Just like the former the latter is initiated into many and diverse mystery cults later on in his life. We hear about distant journeys into foreign lands, long years of study and the deepest wisdom about the natural forces as well as the old gods. — During the last years of public paganism in the Greek-Roman world Apollonius of Tyana had turned into the ideal of the classical philosopher as well as the ancient theurgist ruling celestial as well as chthonic powers. His stories were many and well known. Thus stylising Cyprian as a similarly powerful mage who converted to Christianity free willingly was meant to contrast and break the fascination and appeal that Apollonius still held at the time.

(8) In a similar light, the entire appearance of Cyprian as a pagan as well as his relationship to the demons he calls for is aligned to some themes that can be found in the Greek Magical Papyri. Here is the central parallel in Radermacher’s own words:

‘The mage appears as the ruler of demons, as a theurgist. He commands their coming and leaving, provides them with orders according to his free will and reprimands them when they return unsuccessfully. That is the relationship a master has to his servant; it even holds true with regards to his relationship to the highest of all demons, the ‘father’ who needs to take quite a lot of scolding himself. In short it is the same view we find it in the Greek Magical Papyri when the mage is forcing his will onto the demons.’ (Radermacher, p.30)

A few pages further on the author clarifies in more detail:

‘The Papyrus Harris, the safest witness of ancient Egyptian magic, does not invoke divine assistance as mercy. Instead one commands the gods to help with reference to one own’s divinity; even more so, in some cases one does not turn to the gods at all but to the imminent danger itself and commands it to stay away with reference to one self as a god.’ (Radermacher, p.45)

(9) As part of his study on the origins of the Faust legend Radermacher compares Cyprian’s tale with two other legends of the same time, yet most likely of slightly younger nature. The legends of Proterius and Theophilus provide two early accounts of magical pacts between mages and demons. In portraying the full story of their legends and contrasting it to Cyprian’s tale, Radermacher leads up to an essential point: This is the fact that both of the mages in the stories of Proterius and Theophilus draw their powers from the pacts they have entered with demons. Upon their death or at the end of the contract the demon devours their remains and draws them down to hell. The mages in these stories mainly are a vessel or gateway for the demonic forces and they possess little magical power themselves. Cyprian’s case differs drastically on this point - and therefore also from the much later legend of Dr.Faustus. Cyprian in contrast draws his powers from his own divine nature - and thus can even direct them against the demons he holds a pact with, when this agreement is no longer in his interest. Arguably Radermacher subsequently uses this specific distinction - whether a mage holds a source of magical not dependent on another spiritual being versus a master-servant relationship between demons and mages - to different the theurgist from the goët.

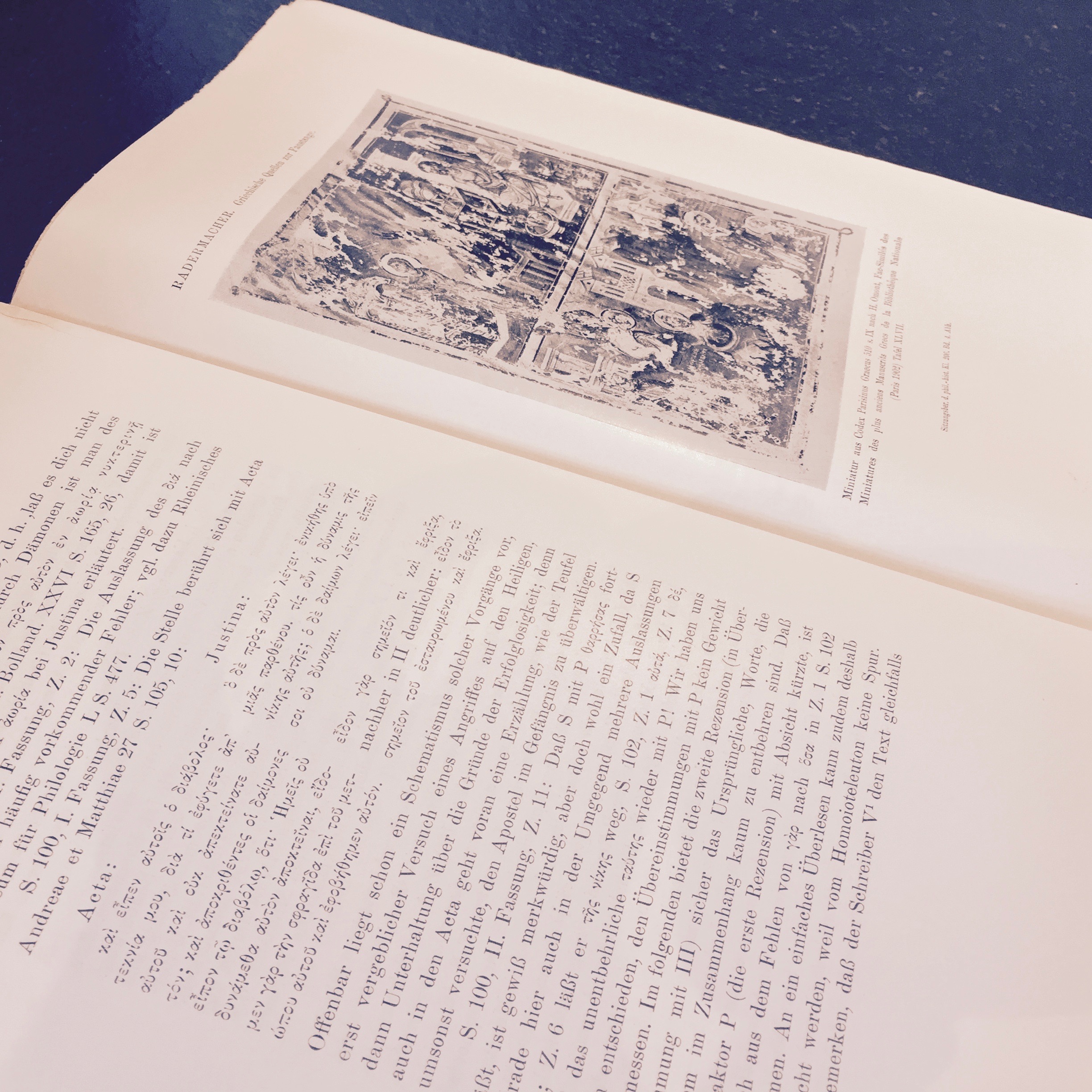

(10) Finally, when I already thought I was done with Radermacher’s small, soft volume - its pages coming loose while reading each chapter - I came across one more thing. And what a wonderful surprise it was: a truly unique portray of St.Cyprian’s story in the appendix. In fact, this might not only be the oldest known portray of the theurgist and later saint, but it also brings together all key elements of the three books. Consider it a comic more than 1100 years old. Below is the image, some highlights as well as the detailed description that Radermacher provides himself. The original source of the image from 1902 can be found here in digital format.

‘The miniature we are inserting here is taken from the Parisinus gr. 150 and belongs to the end of the 9th century: therefore it is older than all of the known manuscripts of the legend and yet clearly influenced by the legend. In the upper right we see Cyprian in his home, still wearing his pagan dress and, as it is ought to be, without the halo of a saint.

To the right of his feet we see a vessel containing magical scrolls, grimoires, behind him the spirit statue, and to his left a basin from which two figures are arising. Cyprian is occupied with a λεχανομαντεια. The globe on the table generally indicates scholarship.

The image in the upper left depicts Justina praying; above the altar the powerful image of Christ is revealing itself to her, meanwhile to her right, cowering, a black demon with an animal face and horrent feathers escapes.

In the lower right we witness Cyprian’s baptism, which still belongs to our legend. Whereas his martyrdom depicted on the lower left is part of a different tradition.’ - Radermacher, p.23