“My happy position in life is matter of mutual satisfaction to us, for whatever good fortune may have befallen me is common to you also, since our friendship is of a kind that suffers nothing to be proper to one of us only.”

The Agrippean Circle

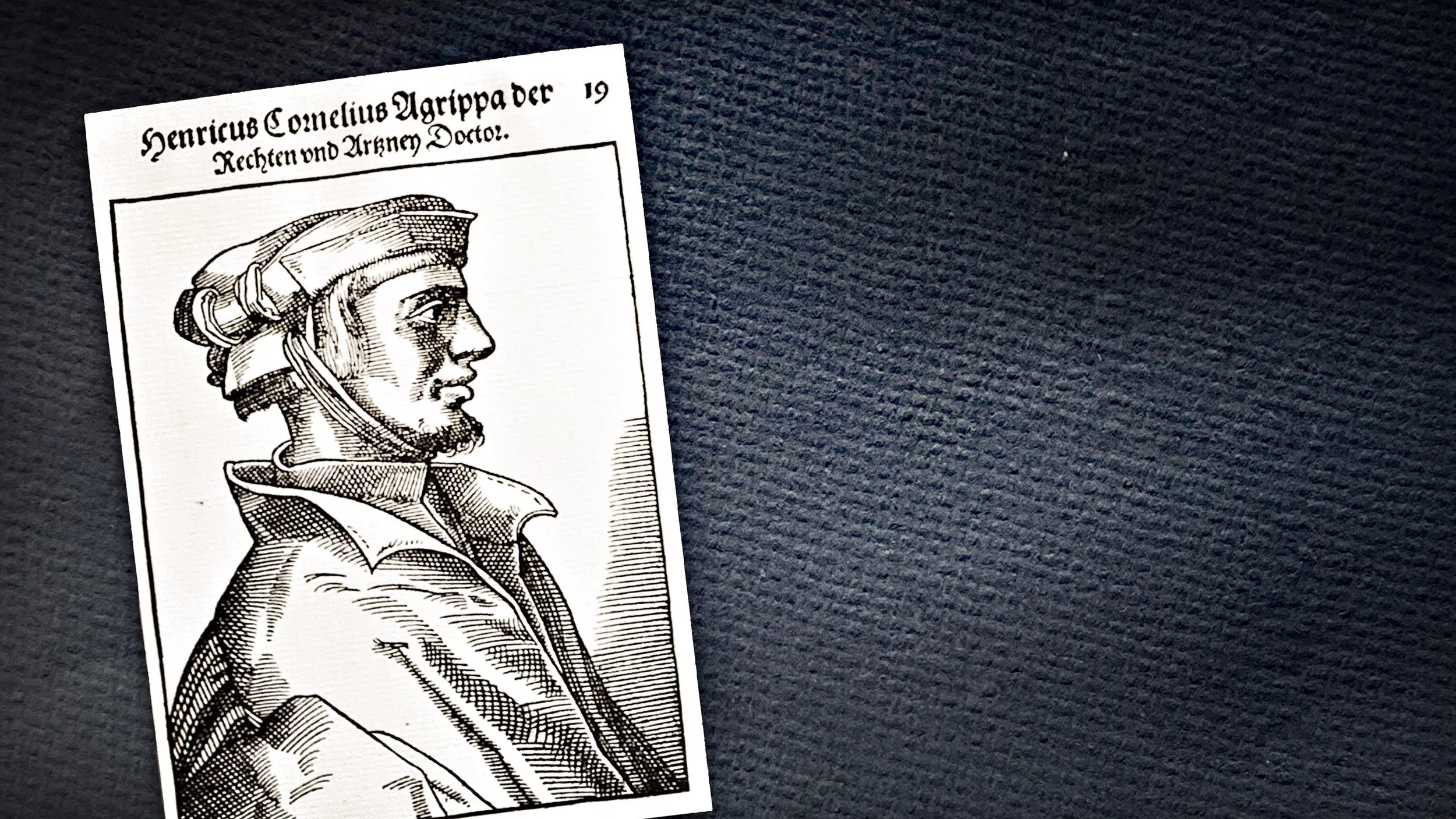

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa of Nettesheim (1486-1535), German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, occult writer and practitioner - no other figure in the history of the Western Esoteric Tradition requires less of an introduction than the author of the famous ‘De Occulta Philosophia’. And yet to this day no English critical biography of the adventures of this furious and stormy spirit exists.

The most recent study is Charles G. Nauert’s 1965 ‘Agrippa and the Crisis of Renaissance Thought’. It is an excellently researched book which, however, speaks relatively little about the Nettesheimian’s life and instead details much more about the intellectual world that formed the tapestry within which Agrippa’s eventful life unfolded (The actual biography spans over only 108 of the total 334 pages). More recently, Wilhelm Schmidt-Biggemann in his groundbreaking ‘History of Christian Kabbala’ (Geschichte der Christlichen Kabbala, Vol.1-3) masterfully compressed the facts of Agrippa’s biographic skeleton in a mere six page summary. However, capturing the spirit that once enlivened it obviously escapes the aim of the academic historian.

So while Agrippa’s literary magnum opus ‘De Occulta Philosophia’ continues to form a cornerstone of modern research into the history of magic, the life that gave rise to it remains largely unexplored. What is most surprising about such lack of attention to Agrippa’s biography, is that it overlooks a particular essential question: What was it that enabled a 24 year old magister from Cologne to singlehandedly compile, rework and synthesise the entire corpus of Western Magic into over 600 pages in less than two years from 1509-1510?

Of course, as widely acknowledged, he worked under the guide of one of the most learned magicians and scholars of his time, Johan Trithemius (1462-1516). However, Agrippa’s study visit to the ‘Black Abbot’s’ monastery in Sponheim only lasted a few weeks. So beyond the immense library in Sponheim, what were the sources that fuelled the fire of Agrippa’s intellect during this most critical creative episode of his life?

The answer to this question is astoundingly obvious - despite how little open consideration or further research attention it garnered over recent decades: next to the literary source works and the wise counsel of Trithemius, it was a secret circle of occult practitioners that supported and enabled the precipitate delivery of the ‘De Occulta Philosophia’. None of Agrippa’s abbreviated biographies fail to mention this circle’s existence, some even point out its importance for the De Occulta, yet no critical study of its origins, network and literary impact exist to date. Thus in the following we aim to provide a brief overview on the few facts known about this occult ‘Agrippean Circle’.

In 1502, at the age of sixteen, Agrippa completed his studies at the University of Cologne with a degree of ‘licentiate of the faculties of the Arts’ (Licentiate der Artistenfakultät, Schmidt-Biggemann, p.450). In later comments Agrippa pointed out how much he despised his initial studies in Cologne as a waste of time (Kuper, p.10; Nauert, p.13). Thus - after serving for the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I. (1459–1519), first as secretary and then as soldier - from 1507 we find Agrippa studying again at the University of Paris, the centre of learning and scholarship of his time - including of the occult arts. It remains unconfirmed if Agrippa indeed acquired the title of a doctor during his years in Paris. However, his personal archive of private letters date from this time, and thus we learn about his interests and relations only from this period of his life onwards.

On this occasion it should be noted that Agrippa’s personal letters present a treasure-trove unexplored by most scholars, and without any significant publishing history in modern times. Agrippa archived hundreds of letters, his own as well as replies received. After his death his inheritors organised and structured these documents into seven complete volumes, which were published 45 years after his death in 1580 (Zambelli, 1969, p.277). Obviously this correspondence was never meant for publication by Agrippa; yet the continuously growing body of letters was precious enough to him to make it part of the possessions which he safely kept with him during his restless and eventful life of continuous traveling. It is from these letters, therefore, that we learn about the secret guild Agrippa had joined - or possibly founded - upon his arrival in Paris.

‘In the year 1507 Agrippa went to Paris to further his studies. There, together with one Landulph and Galbian, he founded a secret society for the research of the occult sciences. A major interest of this society must have been the study of alchemy, as is evident from several letters by Agrippa. However, it seems no aspect of the broad research field of practical metaphysics remained unconsidered, and Agrippa must have made the best studies both theoretically as well as practically, as it emerges from the richness of erudition and positive knowledge captured in the Occulta Philosophia. The society spread from France to Germany, Italy and England; yet the duration of its existence remains unknown.’ (Kiesewetter, p.4)

A Circle without a Name

Almost every one of Agrippa’s biographers have found their own term for what we choose to simply call the ‘Agrippean Circle’: a secret association, a circle of friends, an occult league, a confraternity, or a classical solidacium. Such ambiguity of definition, however, possibly does not have to be read as an acute lack of precise information. Instead, it might be read as a defining characteristic of the particular circle Agrippa and his friends had bound themselves into.

In essence, here is all we know it about it from Agrippa’s collected letters: Neither Agrippa nor his correspondents ever address their circle with a specific name. No official index exists that lists all or even some of the members; we only know of their names through references in the letters themselves. To protect identities, in many cases their names appear as both latinised and abbreviated. A summary of the most commonly called out names is provided below. (Note: this list should not be misunderstood as either concluding or univocally confirmed.) Several of the confirmed identities of the circle turned into lifelong friends of Agrippa, with whom he stayed in letter correspondence despite his hectic life and travels.

No outer insignia or regalia of this circle are ever mentioned or eluded to in the letters, which seems logically given the secret nature of this league. Of the goal and purpose of the circle, however, we do know that it was twofold all the way: On the one hand it formed an occult circle of joined learning and practice of the forbidden arts, with a particular focus on alchemy. On the other hand, and in the most primal sense of a confraternity, it also formed a tightly-knit social circle. The members aimed to support each other both in their magical studies, as well as in ‘amplifying of [their] honour, or the augmentation of [their] worldly welfare’ (Agrippa 1507, after Morley, p.28). This mutual help association - pledged to the enrichment of its members in both worldly and intellectual goods - had significant impact on Agrippa’s life.

A well known example are the details of his extensive travels in 1508: A rogue military expedition led by several of the circle’s members results in a siege on a castle tower in which Agrippa and his comrades are trapped. Only through a ruse conceived by Agrippa does the group manage to escape death, either from hunger or sword, and during their daring escape the men are dispersed. Following this famous episode in the life of the Heinrich Cornelius, we see him travelling across Catalonia, Valencia, Naples and the Ligurian coast in search of traces of the circle’s friends to rejoin the group and ensure their health and wellbeing.

A Circle forged of Oath

In a letter from 1507 Agrippa speaks openly about the nature of the bond that ties the circle’s members together:

‘My happy position in life is matter of mutual satisfaction to us, for whatever good fortune may have befallen me is common to you also, since our friendship is of a kind that suffers nothing to be proper to one of us only.’ (Agrippa 1507, after Morley, p.29)

And in a letter from the following year, this time addressed to Agrippa, we learn more about the manner in which one joined their secret league:

“And he is a curious investigator of arcane matters, and a free man, restrained by no bonds, who, impelled by I know not what reputation of yours, wishes to search through your secrets also. Hence I want you to explore the man thoroughly, and so that he reveals to you the scope of his mind; indeed, in my opinion, his aim is not far from the mark, and experience of great things is in him in certain respects. Then, therefore, fly from north to south, on all sides winged with Mercurial wings, and if it is permitted, embrace Jove's scepters [sic!] and make him, if he wants to swear to our rules, an initiate of our society.” (Landulphus in a letter to Agrippa in 1508, Nauert, p.18)

It is worthwhile to examine the above citation in detail.

The paragraph actually stems from a letter of recommendation. That is, the nameless candidate described in it handed it over sealed to Agrippa, after the former had received it from Landolphus (Kuper, p.12). Now read slowly, the document reveals a number of important aspects of the Agrippean circle:

To enter it, it either seems a candidate had to be inspected by multiple members of the circle. Or, alternatively, the paragraph can be read that Agrippa alone held the privilege of initiating new members.

What might give preference to the latter reading could be the fact that Iove or Jupiter in the letters can be found as a common metaphor for people in positions of power (e.g. Morley, p.29). Embracing Jupiter’s sceptre thus can be read as metaphor for embracing one’s power, in this case Agrippa’s privilege of initiating neophytes into the circle.

Secondly, the candidate had to be a free man (homo liber) - i.e. not bound into service or thraldom of the nobility. More importantly even, they had to show the required ‘scope of mind and intend’. Only a well trained and still curious, unbound mind was admitted entrance.

Finally, the neophyte had to be willing to swear to the rules of the secret league. Only then could they receive initiation.

Conclusions

Despite its brevity, this short examination of some of the unexplored first-hand sources of Agrippa of Nettesheim taught us several important things about the secret circle that the author of ‘The Occult Philosophy’ dedicated so much of his life to.

What we encounter in rare traces amongst his private letters seems to be an occult organisation that truly deserves the name. Precisely because it did not behave like a (formal) organisation, but rather like a (social) organism: It remained ambiguous and fluid throughout its existence, silent about its practice and discreet about its members. Joining it did not come with any kind of worldly privilege, fame or reputation (i.e. the fifteenth century equivalent of today’s highly sought after constant iconic fuel for one’s Instagram account). Instead it gave access to forbidden, and yet living knowledge - and demanded life-long, uncompromising loyalty and secrecy in return. Members were bound by oath as well as their common interest and similarities of minds.

From the moment they received initiation their path was forged into one of ‘gnostic attitude’ (Nauert, p.18). Barely escaping the definition of a heretical sect, as Nauert highlights, this solidly bonded circle became both soil and support for their member’s fate and good fortune.

In times like ours, the world in 2019, sadly such an undertaking seems both surprisingly relevant as well as daring again. For the Agrippean Circle was a truly European organism, long before the national states unfolded their poisonous formal flowers. It united German, French, Italian and most likely English members in one silent circle. It abhorred to be seen and thus to be forced to project an identity, a structure or a single name to be called by. Instead its members enjoyed remaining unknown, and yet treated each other with some of the best human qualities - the ones that blossom best when never presented as ornaments: friendship, loyalty, and the generous sharing of one’s knowledge and resources.

Isn’t it ironic? So many of us strive for communion with particular celestial or chthonic spirits. Yet, here we stand, realising how much harder it might be for a few humans - bound into one race, neither separated by time nor substance - to achieve the very same goal.

“(…) but I cast myself as a bone to Cerberus, by whom I would rather be devoured, than like Prometheus be eaten piecemeal in a struggle with incessant dangers. ”

Selected Sources:

Bechtold-Stäubli, Hanns; Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens, Weltbild 2008 (1927)

Kiesewetter, Karl; Geschichte des Neueren Okkultismus, Georg Olms, 1977 (1896)

Kuper, Michael; Agrippa von Nettesheim: ein echter Faust, Clemens Gerling, 1994

Morley, Henry; Cornelius Agrippa: The Life of Henry Cornelius Agrippa Von Nettesheim, Chapman and Hall, 1865

Nauert, Charles Jr.; Agrippa and the Crisis of Renaissance Thought, University of Illinois, 1965

Schmidt-Biggemann, Wilhelm; Geschichte der Christlichen Kabbala, 15. Und 16. Jahrhundert, frommann-holzboog, 2012

Zambelli, Paola; Agrippa von Nettesheim in den neueren kritischen Studien und in den Handschriften, in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, Volume 51 (1969), Issue 2, Pages 264–295

Zambelli, Paolo; Magic and Radical Reformation in Agrippa of Nettesheim, in: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 39 (1976), pp. 69-103